The wreck of Antikythera, discovered by sponge divers in 1900, is most famous for the clockwork astronomical computer found on board. But it also contained one of the richest hauls of objects ever found from the ancient world - from bronze swords, statues and thrones to golden jewellery and luxury glassware.

The wreck of Antikythera, discovered by sponge divers in 1900, is most famous for the clockwork astronomical computer found on board. But it also contained one of the richest hauls of objects ever found from the ancient world - from bronze swords, statues and thrones to golden jewellery and luxury glassware.

I was reminded of this on Saturday, when I was interviewed for an episode of a programme called Museum Secrets, to be shown on National Geographic in the autumn. It will focus on the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, telling the stories of various objects held there, including the Antikythera mechanism. The rest of the sponge divers' haul is at the Athens museum too, so I thought I'd write a post on it: What else did they find? And is there anything still down at the bottom of the sea?

The Greek government hired the sponge divers to salvage what they could from the wreck, with the help of the navy, during a gruelling ten-month expedition in 1900-1901. According to the official report of the expedition, published (in Greek) by the Archaeological Society of Athens in 1902, their finds included bronze swords, pieces of a bronze throne, and bronze bedsteads engraved with busts of women and lions. There was also jewellery, for example a golden earring in the form of a baby holding a lyre, as well as a full-sized lyre, plus jugs, flagons, kettles, lamps, bottles and a silver wine jar.

Gorgeous and perfectly preserved glassware (described here) included an elegant blue-green bowl carved with a floral design, and a set of mosaic dishes in which stripes of rose, green, purple, yellow and turquoise glass had been coiled into tiny spirals and melted together. There were piles of amphoras (storage jars with pointed bottoms used for transporting food and other goods), one of them with olive pits still inside. But most notable were hundreds of bronze and marble statues, mostly of men and horses, but also some women, and a colossal marble bull.

After two thousand years in the sea the marble statues were horribly disfigured; their smooth sculpted surfaces had literally been eaten away by hungry sea creatures. As they arrived at the museum, they were piled up in a courtyard, to eerie effect (see pic, above).

One of the few marbles that isn't completely ruined is this crouching boy - one of my favourite exhibits when I visited the Athens museum on a sunny November day in 2006 (see pic, left). This statue was half buried by sand, which protected it from the corrosive effects of the sea. The boy's right side is almost perfectly preserved, but on the left, his limbs have been munched away to stumps.

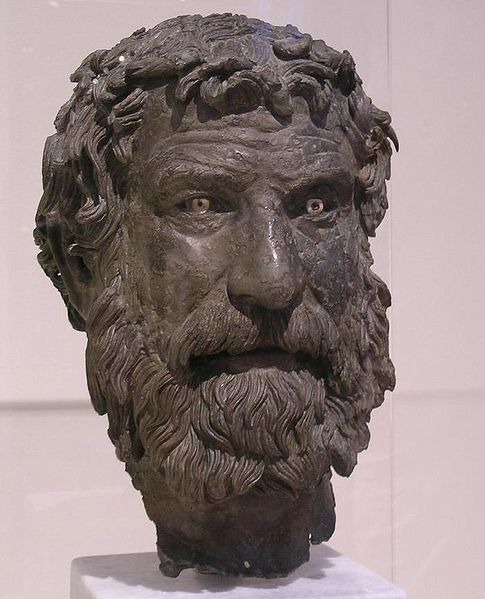

The bronze statues were mostly found in pieces - disembodied heads, hands, feet and smaller fragments. But they were actually in better shape than the marbles because their surfaces had reacted with seawater to form an inert layer that protected the material from further decay.

For example, there's a lovely bronze head of an old man, probably from the third century BC (see pic, below). It's in the style of a Greek philosopher, and because of realistic features such as the wrinkles, it's thought to be a portrait of a particular person, although no one knows who. It comes originally from a full statue - the arms and sandalled feet were also found.

But the most impressive bronze find was a graceful naked male, nicknamed the Antikythera Youth (see top photo). Originally found in more than twenty pieces, it was put back together in the early 1900s by a French sculptor called Alfred André. His efforts were severely criticised, however. In the 1950s the statue was taken apart again and reassembled in a slightly different position - to everyone's satisfaction it seems - by a Greek renovator called Christos Karouzos.

The Antikythera Youth is thought to be from the fourth century BC, perhaps not one of the very finest Greek statues ever made, but certainly of high quality. It isn't known where it is from, who the sculptor was, or who the statue was meant to be of.

There are some clues though. At nearly two metres tall the statue is slightly larger than life, so experts think it represents a god or hero rather than a mortal. And traces of bronze still attached to the statue's fingers show that it originally held something spherical in its raised right hand. Suggestions from Greek mythology have included Perseus holding up the severed head of Medusa (her hair in a tight spherical bun); Paris displaying, or preparing to throw, the apple of discord; or a young, beardless Herakles (the Greek version of the Roman hero Hercules), perhaps picking a golden apple in the Garden of the Hesperides. There's much more on the statue, including photos of the reconstructions and diagrams showing how it is put together, in this 2006 PhD thesis (pdf file).

Surprisingly the ship itself turned out to be not Greek but Roman. Judging from the origin of storage jars, plates, coins etc on board, she sailed from the Asia Minor coast in 70-60 BC. When she sank she was probably on her way west to Rome, perhaps carrying looted cargo (Roman armies, led by the general Pompey, were sweeping through this region at the time).

Could there be more treasures still lying at the wreck site? The sponge divers believed that there was plenty left when a combination of bad weather and exhaustion finally forced them to end their salvage expedition in the summer of 1901. The diving pioneer Jacques Cousteau led another salvage project at the site in the 1970s, which he filmed for a documentary called Diving for Roman Plunder. His divers brought up plenty of small objects, including ship nails, coins, a lamp, two elegant bronze statuettes on rotating bases, and a human skull.

So it's unlikely that there is still anything lying exposed at the wreck site. But Cousteau had limited time for his expedition too, and without the gas mixtures that are available today for deep diving the divers could only spend short bursts of time working at the 60-metre-deep site. So it's very likely that there are still buried objects there, say cargo stored in the lower parts of the ship, now covered by the sediment that settled on the wreck over millennia. This would be hard for any subsequent expedition to get at (if indeed it was felt appropriate to carry out such an invasive excavation). But the items might be better preserved than those found so far.

The hull of the ship itself may also survive under the sand. Cousteau's colleague Frederic Dumas described poking around in the sand with a pipe during a 1953 dive at the site in his wonderful book 30 Centuries under the Sea:

"...the pipe ran right into the hull of the sunken ship, which was perfectly preserved under a foot and a half of sand. If only I had more time!"

A third possibility is that more items from the wreck are lying undiscovered in deeper water. The ship settled on a sloping shelf of rock, near to a cliff that drops down to greater depth. So some objects could presumably have fallen down there as the wreck sank. The Archaeological Society's 1902 report also says that several large boulders, lying on top of the wreck, were heaved out of the way and over the cliff before it was realised that these were actually enormous (but very corroded and overgrown) statues. And it describes how a large statue of a horse that tore loose from its chains as it was being winched onto a boat, tumbling down into the depths.