When the Guardian's Alok Jha asked me to speak on a panel at this year's World Conference of Science Journalists on the importance of narrative in science journalism, I agreed straight away. After a decade writing and editing for Nature and New Scientist I felt well qualified to discuss the topic.

Subsequently, the title of the panel changed to "literary storytelling" - a small tweak but one that filled me with fear. Writing clear, engaging science news is one thing but when it comes to "literary" writing, well, that's a different world in which I feel a complete beginner.

The other speakers on the panel - David Dobbs and George Zarkadakis - are experienced authors, with many beautifully written long-form articles and books to their names. I have written just one book.

So I decided to talk about what it was like making that first step in the transition from "science reporter" to "author". What was the biggest mistake I made, and how did I have to change the way that I write?

A lot of the points I'm about to make may seem obvious to anyone trained as a "proper" writer, but for me, coming from a science background and used to writing for outlets like New Scientist and Nature, it required quite a paradigm shift. In fact, I think there are certain things about some kinds of science journalism that actively inhibit the parts of the brain and ways of thinking that you need for creative writing.

I was used to writing in a very logical, left-brain way - news journalism is pretty much about finding out facts, and putting them in the right order. Space is at a premium, so you have to convey information in a very economical way, with a fact in every sentence. What was done, who by, how, what did they find?

You have to explain complex technical concepts clearly and unambiguously. You talk about what things mean in a very analytical way. You don't generally put in anything of yourself - your thoughts or emotional reactions (or if you do, your editor will take them out). Constructing a story is a bit like constructing an argument.

Then I came to write my book, which is about a mysterious astronomical computer found on an ancient shipwreck. The first chapter should have been a dream of a tale. In 1900, sponge divers crossing the Mediterranean were blown off course by a storm, and took shelter by a rocky islet. The next day they dived into the water and discovered a wreck, filled with treasures from ancient Greece. They spent the next 10 months salvaging the artefacts in a treacherous mission during which one of them died of the bends, and two were paralysed.

I did painstaking research, raiding historical archives and translating old Greek documents to find out as many details as I could about the episode. When I wrote the chapter, it was clear, well-structured and packed with facts. But I discovered that what works for a New Scientist news story doesn't necessarily work for an 8,000-word book chapter. I gave my draft to a journalist friend to read and he came back to say that it was dense, flat and unmoving - a barrage of facts that was exhausting to read.

I realised that I needed to relax, and slow the pace right down. I couldn't just relay information, I had to really tell a story. It was a harsh lesson that to sustain a reader's attention over a long span, you have to say what things mean as well as just what happens. You have to transport the reader into the story, to carry them along with you.

I'm sure there are much better names for this but as I went through the book I started thinking of it as "inside out writing". Instead of processing and conveying facts in quite a superficial way, you need to internalise all of the information that you're gathering, to think very honestly and deeply about what it means, have an emotional reaction to it, and then try to bring that out in your writing.

I would do all my research for a particular scene, then try and turn off my left brain. I'd shut my eyes and imagine being there; think about the sounds, sights, smells; what the characters would have been feeling; the greater significance of the events I was describing.

I think there are a couple of overlapping aspects to this. The first is to describe a scene in a lifelike way, put the reader right in the middle of things. Think about involving all five senses to capture the feeling of a particular moment. Maybe it's looking up to see shafts of sunlight shining down through the water, or hearing the sound of helicopters whirring overhead like ravenous giant mosquitoes (the mosquitoes are from Andrew Smith's book Moondust: In search of the men who fell to Earth, which I think does this really nicely).

To do this you don't have to be writing a narrative-led or biographical book, it can be important even in the more traditional type of science book, that discusses a particular subject. For example, Being Wrong by Kathryn Schulz (which I absolutely love) is about how holding false beliefs is part of being human, and how good we are at convincing ourselves that we're right even in the face of overwhelming evidence that we're wrong. There's a chapter about how often witnesses make mistakes when identifying criminals, and how the strongest, most emotionally charged memories are the most likely to be false.

In this chapter, Schulz tells the story of a woman who is raped while running alone on a beach. Her description is powerful and immersive, she makes you feel that woman's fear, her pain, her strength of will, her determination to remember, how she made sure that every detail of her attacker's face was etched onto her memory. After reading it, you feel some of the same shock and disbelief when you later find out that she had emphatically identified the wrong man.

The other aspect to inside out writing is that you need to get beyond simply saying what happened, to say what things mean, and what they mean to you.

Saying what something means is of course the role of a writer. You're trying to capture the essence of something, to give it a meaning that's personal yet universal. Often when I was writing I'd have this elusive feeling about why something is important - about how events or ideas were connected or why I wanted to include a particular anecdote. But I'd struggle to put it into words. That's the important bit, that's what you have to try to drag out from inside, and to express on the page.

In her book Longitude, Dava Sobel opens one chapter with her musings on time: "Time is to clock as mind is to brain. The clock or watch somehow contains the time. And yet time refuses to be bottled up like a genie stuffed in a lamp. Whether it flows as sand or turns on wheels within wheels, time escapes irretrievably, while we watch."

This passage doesn't contain any facts, and it doesn't move on the story at all. But I think it was important for Sobel to stand back at that point and give a very human account of what the essence of her story is about.

It is possible to do this even in shorter news pieces too, but it's rare. One example is an 800-word news article written by James Meek, which ran in the Guardian in 2003 (thanks to Ian Sample for passing it on to me). The article was about Iraqi families and soldiers who tried desperately to get inside government buildings after the fall of Saddam Hussein, clinging to the belief that their loved ones who had gone missing during the regime might still be alive, kept in secret underground cells.

The first two paragraphs describe fairly conventionally what is happening, then the first sentence of the third paragraph hits you like a bullet: "Those who have lost what they loved the most are always the richest in hope." For me, this one line crystallises the human meaning of the story.

Of course this is what proper writers do all the time. But as a news journalist, and I think especially a science journalist, it can feel like a huge change. In trying to take this approach I felt that I was breaking a lot of ingrained rules. To tell a real story you have to be subjective, creative, emotional even, but to write about science you have to be accurate, clear, unambiguous, and not mess with the facts themselves. There is always going to be a tension between those conflicting principles.

Despite all my experience as a science journalist, the biggest thing that writing a book taught me was how much I have to learn about what it actually means to write well about science (or anything else, for that matter). If there are any other scientists or science journalists out there dealing with similar issues I'd love to hear about your experiences.

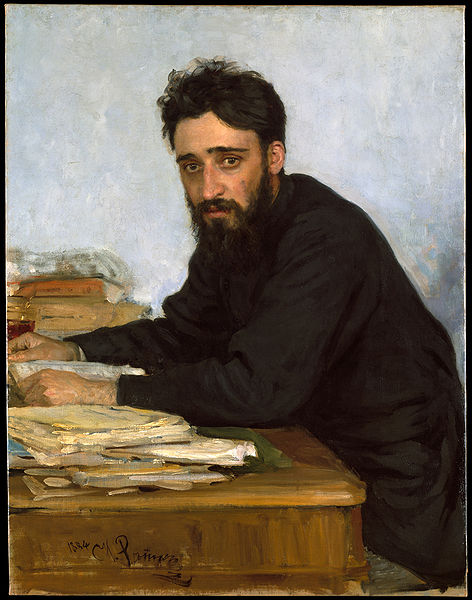

*** The picture is a portrait of the Russian short story writer Vsevolod Garshin, just because he looks like he found writing tough too...