Part of the Terracotta Army of China's First Emperor goes on show at the

High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, today. I was lucky enough to see the sell-out exhibit at the

British Museum in London earlier this year, and I don't think I've ever experienced anything that brings the ancient past so vividly to life as these terracotta soldiers do.

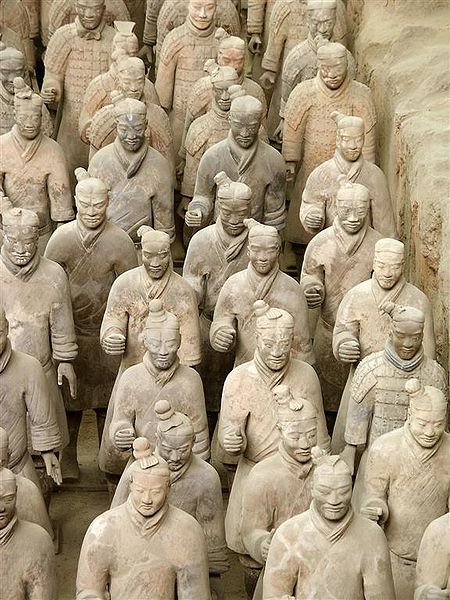

They were built for Qin Shihuangdi, known as China's first emperor because he unified the country for the first time; he reigned from 221 to around 210 BC. The story of his terracotta army is world-famous - farmers digging a well in the outskirts of Xi'an in 1974 discovered the life-size figures buried in the ground. Archaeologists have since found around 8000 soldiers in a series of pits, standing in battle-ready formation to guard Qin's tomb.

The stunning thing is how detailed and individual the figures are - they were handmade with varying ages, hairstyles, uniforms and facial expressions. As well as soldiers there are officials, scribes, acrobats, strongmen (presumably Qin thought he would need entertaining as well as defending after his death), and horses with bronze chariots. In 2001 archaeologists discovered a diverted underground river, by which terracotta musicians played to lifesize bronze water birds.

But I think the most intriguing thing about the whole site is the Emperor's tomb itself. It has never been excavated, for fear that exposure to the air would damage the contents, so what's inside is a mystery. However we do have a description of the mausoleum written about a hundred years after Qin's death, by a historian called Sima Qian:

"As soon as the First Emperor became king of Chin [Qin], excavations and building had been started at Mount Li, while after he won the empire more than seven hundred thousand conscripts from all parts of the country worked there. They dug through three subterranean streams and poured molten copper for the outer coffin and the tomb was filled with models of palaces and pavilions and offices as well as fine vessels, precious stones and rarities. Artisans were ordered to fix up cross-bows so that any thief breaking in would be shot. All the country's streams, the Yellow River and the Yangtse were reproduced in quicksilver and by some mechanical means made to flow into a miniature ocean. The heavenly constellations were shown above and the regions of the earth below. The candles were made of whale oil to ensure their burning for the longest possible time."

It sounds like an Indiana Jones movie! Could this incredible description be accurate? Archaeologists have been using radar and other remote sensing techniques to try to glean what's inside. It's hard to get much information about this work, the results tend to come out as short statements from the official Chinese news agency, but I've gathered together what I could find.

There's definitely a huge underground palace inside the burial mound (see the second half of this news story). Qin's tomb is at the bottom, with symmetrical staircases leading down into the tomb, and wooden structures inside it. The tomb also has an effective drainage system, which has stopped groundwater seeping in.

Above this is a 30-metre high pyramid shaped chamber, with stepped walls, which archaeologists think could have been meant as a passageway for the Emperor's soul. Researchers believe there is a huge number of silver and bronze coins inside. And they have found a very high density of mercury in the soil, suggesting that the story about a quicksilver ocean could be true. There are some images here, but the paper is pretty technical.

One option to open the tomb without damaging the contents might be to seal off the whole site with a huge airtight tent. But apparently only one company in the world makes such tents, and they don't make them big enough. In 2007, Chinese archaeologists announced that they have no plans to excavate the tomb to see for sure what's inside.

According to China Daily, the deputy curator of the Terracotta Army, Cao Wei, said: "I would not witness the excavation in my life. In the foreseeable future the mausoleum will maintain the status quo."

I admire him for that. I completely agree that the tomb should not be opened unless researchers are certain that they can protect what's inside. But this is such a tantalising opportunity - unlike virtually all of the Egyptian pyramids, this site does not appear ever to have been ransacked by looters, and the riches and technology inside could be stunning. If I was in charge of the operation I don't know if I would have the patience to accept never knowing what it holds.