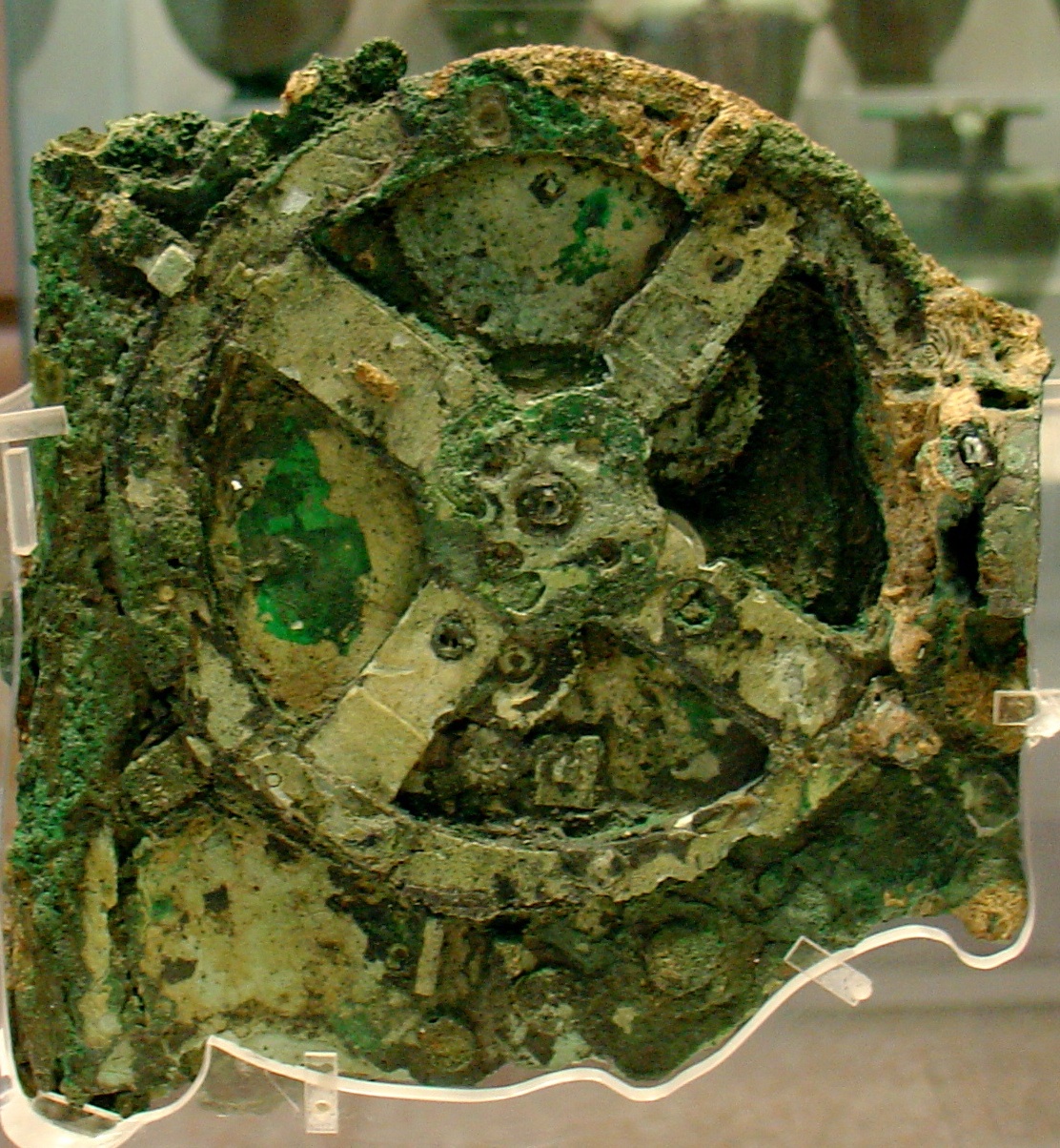

Last Friday I caught the train to snowy Cambridge for a half-day conference on the Antikythera mechanism, organised by the Whipple Museum of the History of Science. Several of the researchers from the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project spoke about their work on the device, so it was a good opportunity to catch up with them and find out where things have got to.

Last Friday I caught the train to snowy Cambridge for a half-day conference on the Antikythera mechanism, organised by the Whipple Museum of the History of Science. Several of the researchers from the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project spoke about their work on the device, so it was a good opportunity to catch up with them and find out where things have got to.

First, Mike Edmunds of Cardiff University and his London-based colleague Tony Freeth summarised the project so far. They didn't add much to what has been said before, however, and it was Alexander Jones, over from the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World in New York, who gave the most interesting talk of the day. He has been collaborating with Tony Freeth and others to decipher the inscriptions on the mechanism, particularly those letters hidden beneath the surface of the surviving fragments and revealed only recently by 3D X-ray imaging.

Most recently the research group has been studying the text on the front of the mechanism, and they have a paper planned on this very soon. Unfortunately Jones didn't pass on any juicy advance details and instead focused on the back of the mechanism, which was the subject of a Nature paper published in July last year.

In that paper, the team reported that the month names used on a 19-year calendar on the back of the mechanism came from a civil calendar, not an astronomical one as assumed, and that a smaller dial didn't show a 76-year calendar as previously thought, but a 4-year cycle marking the timing of the Olympic and other Greek games.

In his talk, Jones told us how surprised he had been to learn that this civil calendar was tightly regulated to lunar and solar cycles. Previously it had been thought that only astronomers used such sophisticated calendars, whereas the calendars used by ordinary people were much more ad hoc. But that clearly wasn't the case. Among other things, the mechanism's dial explained which months should have 29 days and which should have 30 days, and exactly which days to skip.

Jones also talked about the month names used on the calendar, including Phoinikaios, Kraneios, Lanotropios and Machaneus. Different month names were used in different regions of Greece, so in theory these should help pin down where the mechanism was made. Unfortunately knowledge of exactly what months were used where is very patchy, but the closest matches to the ones on the Antikythera mechanism are with regions colonised from the city of Corinth - candidates include Corfu, Illyria and Epirus in northwest Greece, and Syracuse in Sicily. Syracuse is a particularly exciting prospect because this is where Archimedes lived - and ancient writings suggest he once made a device similar to the Antikythera mechanism. But Jones revealed a hint that may implicate northwest Greece instead.

It's on the 4-year Olympiad dial. The different games listed on the dial are Isthmia, Olympia, Nemea, Pythia and Naa (plus one other that hasn't been deciphered). Isthmia, Olympia, Nemea and Pythia were all major games, of importance across the Greek world. But the Naa games, held in Dodona, were a much smaller affair, of only local interest. So Jones speculates that the dial might have been designed for someone who lived nearby. Dodona was in Epirus, one of the regions also implicated by the month names on the calendar, so perhaps the device was made in Epirus. Deciphering the final name on the list might help to confirm or rule out this theory.

Jones said he thinks the Antikythera mechanism wasn't so much a computer, designed for making specific calculations, as a simulator, intended to demonstrate the workings of the universe to a broad intellectual audience. He also revealed that it may be even older than thought, perhaps from the early second century BC. The inscriptions have been dated to around 100 BC. But because we don't know where the device is from, that's only a very rough estimate. Jones pointed out that many of the Corinthian colonies were devastated or taken over by the Romans well before 100 BC: Syracuse in 212 BC, Epirus in 167 BC, Corinth in 146 BC. After Roman conquest the inhabitants would presumably have stopped using their Greek calendar, suggesting that the Antikythera mechanism was built earlier than this. I think he's right when it comes to northwest Greece, but Syracuse was still Greek-speaking and relatively prosperous into the first century BC so its inhabitants could have carried on using this calendar for quite a while.

Also still unanswered is the question of how the mechanism ended up on the ship on which it was found.This was a Roman ship sailing from Asia minor in the eastern Mediterranean, carrying valuable goods (probably war booty) back to Rome. Yet the Corinthian colonies were all in the western Mediterranean. This caused a bit of discussion after the talks between Jones and Edmunds, who believes that devices like this, if not the Antikythera mechanism itself, were being made at the time in Rhodes in the east. I think he's probably right, and that the tradition of these devices spread across the Greek world.

Paul Cartledge, professor of Greek classics at the University of Cambridge, wrapped up proceedings with some entertaining comments about the wider significance of the Antikythera mechanism. In particular, he's interested in what the device tells us about the culture and mindset of the ancient Greeks. His main point was that although historians have often viewed the Greeks as not very technologically minded, the Antikythera mechanism shows that science and technology were central to their world. What's more, it suggests they were moving away from belief in superstition and omens towards a much more modern mindset in which the universe is explainable, and operates according to predictable rules.

I still find that astounding. More than two thousand years ago, you could say that the Greeks were having their own Scientific Revolution.