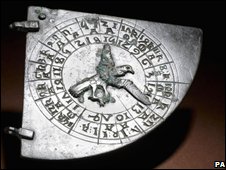

An extremely rare astrolabe quadrant has been rescued - for the second time. Back in 2007, I wrote a news story for Nature about this intriguing device after it was plucked from a junk pile during building works in the historic British city of Canterbury. Foundations were being dug for an extension to a restaurant that was housed in a period property, and Andrew Linklater of the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, who was assigned to watch over the works, found the dirty brass plate nestled among shards of pottery in a 14th-century rubbish pit.

Linklater couldn't identify the plate, so he took it to the British Museum. The experts there "held their hands up and went wow", he told me. It turned out to be only the eighth astrolabe quadrant ever discovered. The way it had been found was even more unusual - the device would have been the height of technology at the time, and such instruments are usually handed down through collections, not found discarded in archaeological sites.

Astrolabes were used for making astronomical observations and allow their owner to tell the time and calculate latitude. They are normally circular, but the rarer quadrants were "pocket" versions - more complicated to use but easier to carry around. Back in the 14th century, the street where the quadrant was found was lined with inns for pilgrims coming to Canterbury, so perhaps it belonged to one of these travellers.

I'm writing about it again now because the UK Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest has just released its annual report. This committee defers export licences on precious artistic and cultural artefacts in danger of being sold abroad, so that they remain in the country until money can be raised by a British buyer (I bet the Greek government wishes it had had such powers back when the Elgin marbles were being shipped to the UK). Eight items were saved last year, and the Canterbury quadrant was one of them. When I wrote my news story, the quadrant was about to be sold by London auctioneers Bonhams, and it was expected to net the restaurant owners between £60,000 and £100,000. The British Museum wanted to buy it but was outbid by an anonymous telephone bidder, so the government acted. In the end, thanks to the temporary ban on export (and some generous grants) the British Museum was able to buy the quadrant at a second auction in July 2008 - for £350,000!

The extension to the restaurant is now complete by the way, and the owners have apparently named it the Quadrant Bar.