There’s a quiet revolution going on in palaeontology, that's telling us more than ever before about the lives and biology of ancient creatures. Instead of spending months or years chipping away at fossils to glean details of extinct species’ anatomy, researchers are increasingly turning to state-of-the-art X-ray imaging to create exquisitely detailed three-dimensional images of fossils without even having to crack open the rock.

This takes extremely powerful X-rays, but can now either be done at particle accelerators such as the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, or by a new generation of lab-based scanners (like the one I wrote about in Decoding the Heavens, used to image the Antikythera mechanism back in 2005). Some enthusiasts even think that with the help of this kind of technology, palaeontologists could soon be hanging up their hammers and chisels altogether.

I'm excited about this because it is allowing researchers to move beyond dry questions of anatomy and taxonomy and start looking at how ancient animals lived. A recent imaging study of Archaeopteryx’s inner ear shows it had similar hearing to the modern-day emu, at the lower end of the sensitivity range of living birds. Meanwhile 3D X-ray images of the fossilised brain of a 300 million-year-old fish (probably the oldest brain ever discovered) reveal large optic lobes and a small cerebellum, suggesting it was a sluggish bottom dweller with keen eyesight. Another project looking at microscopic daily growth lines in the teeth of fossil primates shows that Neanderthals had a long childhood like that of modern humans, rather than growing up fast, like chimps.

All of these studies involve structures that are hidden within fossils and are too small and/or delicate to be exposed using traditional dissection techniques. I wrote about this for New Scientist last month (you can read the article here, or check out the accompanying video of species found hidden in amber). But now there’s a new study to add to the list, involving some mind-boggling reproductive practices.

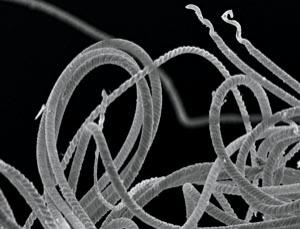

The species in question is a small aquatic crustacean called an ostracod. Modern-day ostracods have an interesting claim to fame – they produce giant sperm up to ten times (yes ten times) longer than their own bodies (up to 1 cm long, see pic). It’s thought that males evolved these super-swimmers in the face of intense competition from the sperm of rival mates. But producing them takes a huge amount of energy, so some experts had assumed this wouldn’t survive for long as an evolutionary strategy.

Now researchers have used X-rays from the ESRF particle accelerator to study 100 million-year-old ostracod fossils. The animals are only a millimetre long, but the team was able to see details of the animals’ complex reproductive organs, confirming that even this ancient species relied on giant sperm, suggesting the strategy is stable after all. And two of the female specimens had hugely inflated sperm receptacles, revealing that they had only just mated.

A 100 million-year-old insemination – now that’s an impressive window into the past.