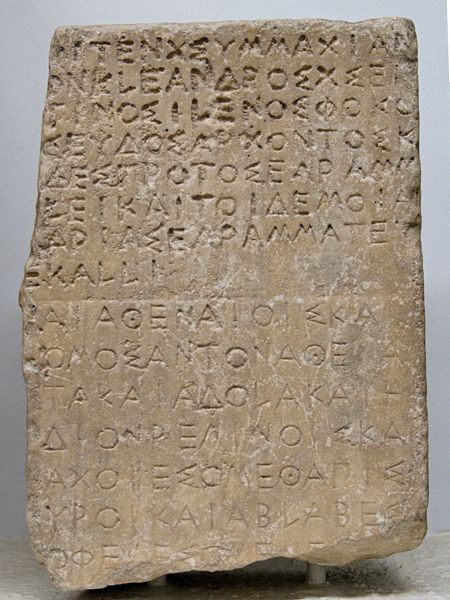

Greek stone inscriptions might look pretty dry and impersonal to us, but actually the lettering hides personal clues as to the identity of the scribe, just as our own scribbled notes do today. Being able to match up which inscriptions were made by the same writer helps scholars to pin down the dates of particular texts more precisely, as well as revealing links and associations between different inscriptions. This has previously taken years of training, and a fair amount of subjective judgment, but now it looks as though computers could start doing the job instead.

Epigrapher Stephen Tracy of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton challenged computer scientists who knew nothing about Greek inscriptions to attribute 24 ancient writing samples to their rightful makers - the texts were written by six different people between 334 BC and 134 BC. To his surprise, the team, led by Michail Panagopoulos at the National Technical University in Athens, got every single one right. Tracy reckons their technique is a "real breakthrough" that could now allow Greek inscriptions to be analysed much more quickly and objectively.

Just as in modern handwriting, ancient writers had individual quirks in the way they formed particular letters. So Panagopoulos and his team overlaid digital scans of different examples of the same letter - the As for example - then used a computer algorithm to calculate the probability that they were carved by the same person. They did this with six different letters across all 24 inscriptions, and have written up their report in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence.

Archaeologists have tens of thousands of examples of ancient Greek inscriptions, and the idea now is to build a computer database of as many of them as possible, including scans, attributions and dates. Then any new finds could be slotted into that record. Presumably the technique would also work for other ancient texts, such as cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia. Though I wonder whether some epigraphers might get a bit defensive about this part of their work being taken over by computers.