The ancient Greeks invented the steam engine (a small demo version anyway), and when they came up with the Antikythera mechanism, they weren't that far from building a mechanical clock. So one of the questions I'm often asked is: why didn't the Greeks make better use of their inventions? Why did we have to wait so many centuries for the Industrial Revolution?

The late science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke blamed the Romans for destroying Greek culture - if the Greeks had been allowed to build on their achievements, he said, they could have reached the moon by 400 AD, and by now, we'd presumably be exploring other stars.

Inspiring as this idea is, the answer is clearly more complicated than that. It takes more than an invention to change the world - all sorts of social and political factors have to be in place for the revolution to happen.

Robin McKie's review of The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry and Invention pinpoints this nicely. The book is by William Rosen and the powerful idea in question is James Watt's invention of the separate condenser for the steam engine, which he came up with while strolling through Glasgow Green in 1765.

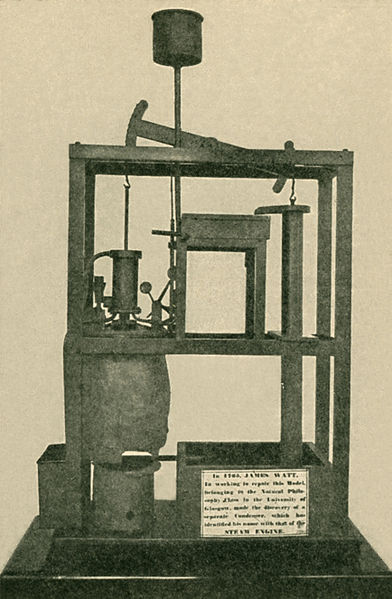

The steam engine that Watt was working on at the time (see pic) was a clunky, inefficient beast. A build-up of steam forced a piston through a cylinder. Spraying cooling water into the cylinder then caused the steam to condense, sucking it back to its original position. Repeating this cycle meant that the whole apparatus had to be heated and cooled over and over, which wasted huge amounts of energy. On his fateful walk, Watt realised that having a separate condenser would still create a vacuum, but allow the engine itself to be kept at a constant temperature.

Rosen describes this as "one of the best recorded, and most repeated, eureka moments since Archimedes leaped out of his bathtub". Cue the Industrial Revolution. "Within a few decades," says McKie, "webs of railways, factories and mines were spreading across the nation."

Yet we know that other inventors through history were tinkering with ideas not so far removed from Watt's. The engineer Hero of Alexandria, for example, demonstrated a spinning steam-powered contraption called an "aeolipile" in the first century AD.

Rosen's point is that transforming industry took far more than Watt's brilliant idea. Watt's breakthrough would likely have come to nothing if the ground hadn't been prepared by other technological advances, such as the ability to make parts of industrial machinery with precision, and developing a better understanding of the basic science behind steam engines. Just as crucial were intellectual and legal changes - such as new patent laws - that "rewarded both the inventor and society for making and accepting change".

Makes you wonder what other world-changing inventions are out there, just waiting for society to become ready for them. I've a feeling that Clarke, if he was still with us, would have some ideas...