In September 1653, a small warship called the Swan formed part of Oliver Cromwell's forces as they attacked Duart Castle, a staunchly royalist stronghold in Mull on the west coast of Scotland. A thousand troops disembarked from the fleet's six ships, only to find the castle abandoned. But worse was to come. On 13 September a nasty gale sank three of their anchored vessels.

Robert Lilburne, the senior government commander in Scotland, wrote to Cromwell: "While our men staid in this Island the 13th instant there hapned a most violent storm, which continued for 16 or 18 houres together, in which wee lost a small Man of Warre called the Swan that came from Aire." Most of the soldiers were still onshore, but they had to watch, helpless, as more than twenty of their comrades met their deaths.

The wreck of the Swan was discovered in the 1970s and excavated in the 1990s. Artefacts including an iron gun, the brass lock-plate from a pistol, an ornate sword hilt and a hoard of silver coins were recovered and taken to the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

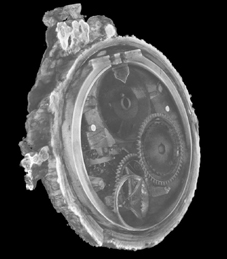

Why am I telling you this story now? Well, one of the most intriguing items salvaged from the wreck was a 17th-century pocketwatch. It was covered in barnacles and corroded almost beyond recognition (see top pic). A fuzzy X-ray image taken at the museum showed that some of the gearwheels inside had survived, but didn't provide any useful information about what kind of watch it was, or what state the mechanism was in. The only way to find out more would have been to break the watch open, something conservators hate to do, so it was put to one side.

Why am I telling you this story now? Well, one of the most intriguing items salvaged from the wreck was a 17th-century pocketwatch. It was covered in barnacles and corroded almost beyond recognition (see top pic). A fuzzy X-ray image taken at the museum showed that some of the gearwheels inside had survived, but didn't provide any useful information about what kind of watch it was, or what state the mechanism was in. The only way to find out more would have been to break the watch open, something conservators hate to do, so it was put to one side.

Until now. Museum scientist Lore Troalen and her conservator colleagues Darren Cox and Theo Skinner have recently used a state-of-the-art X-ray scanning technique to probe the watch's innards. This is the same imaging technique that was used so successfully on the Antikythera mechanism in 2006 - indeed the researchers got the idea from reading about the Antikythera mechanism in Nature.

Troalen and Cox packed the watch in a Tupperware sandwich box and took it to Andrew Ramsey of X-Tek Systems in Tring, Hertfordshire, part of the team who imaged the Antikythera mechanism (you might remember him and his colleagues from my book). The technique, called 3D computed tomography (CT) involves imaging an object from thousands of different directions, then combining all of the data to produce a three-dimensional virtual reconstruction of the object's internal structure.

Troalen and Cox packed the watch in a Tupperware sandwich box and took it to Andrew Ramsey of X-Tek Systems in Tring, Hertfordshire, part of the team who imaged the Antikythera mechanism (you might remember him and his colleagues from my book). The technique, called 3D computed tomography (CT) involves imaging an object from thousands of different directions, then combining all of the data to produce a three-dimensional virtual reconstruction of the object's internal structure.

Troalen says she didn't hold out much hope that the watch would be in great condition, but she hoped at least to find a mark or signature that could help to identify the original owner of the watch.

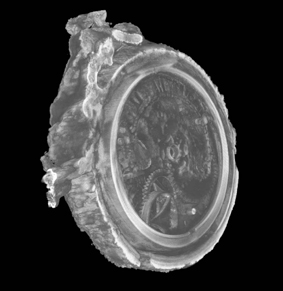

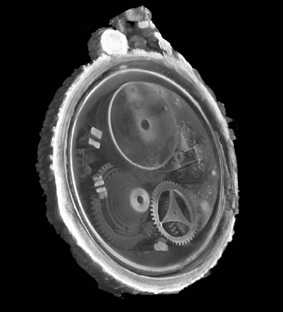

The results, published in The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, are stunning. Although the steel parts of the watch - its single hand, and the studs and pins that originally held the mechanism together - have corroded away, the majority of its components are brass, and in extremely good condition (see pics 2, 3 and 4). I've just written an article about the project for Nature, which has a slideshow of more of the X-ray images than I'm showing here, as well as an animated fly-through of the watch's insides.

The X-rays show that the watch was driven by a single gear train, as was typical for watches of the period. Roman numerals marked the hours, and there are plenty of decorative touches, including floral engravings, and an English rose in the centre of the dial. The watch, as well as its virtual reconstruction, are on display until 2011 in the Treasured gallery of the National Museum of Scotland.

The X-rays show that the watch was driven by a single gear train, as was typical for watches of the period. Roman numerals marked the hours, and there are plenty of decorative touches, including floral engravings, and an English rose in the centre of the dial. The watch, as well as its virtual reconstruction, are on display until 2011 in the Treasured gallery of the National Museum of Scotland.

Other, more impressive, watches from this period do exist, but researchers are excited about this study because (along with the Antikythera mechanism) it shows how much detail can be preserved in objects after hundreds or even thousands of years under the sea.

Since the work on the Antikythera mechanism, 3D CT is starting to revolutionise the study of fossils (something I've written about before) and hopefully this watch project will be one of many on archaeological finds. The technique is likely to be particularly useful for studying objects, from terrestrial or underwater sites, that are embedded within layers of corrosion products, and that contain small, detailed structures, for example inscriptions or mechanical parts.

So did Troalen and her colleagues find that signature? They did indeed - that of Nicholas Higginson, a watchmaker who was based in London in the years before the Swan went down (see last pic). The watch would have been expensive, so its most likely owner was the Swan's captain, who was called Edward Tarleton. Archaeologist Colin Martin, who led the original excavation of the Swan, says that the watch was found in the vicinity of the stern cabin, where the captain would have lived, along with a sword, and "quite a bit of booze".

So did Troalen and her colleagues find that signature? They did indeed - that of Nicholas Higginson, a watchmaker who was based in London in the years before the Swan went down (see last pic). The watch would have been expensive, so its most likely owner was the Swan's captain, who was called Edward Tarleton. Archaeologist Colin Martin, who led the original excavation of the Swan, says that the watch was found in the vicinity of the stern cabin, where the captain would have lived, along with a sword, and "quite a bit of booze".

Tarleton didn't go down with the ship, by the way. He ended up as Lord Mayor of Liverpool.

***Thank you to Trustees of NMS for letting me use these images***

UPDATE (13 Oct): I forgot to say that X-Tek is now owned by Nikon Metrology. There's more info about their CT technology here (they normally use it for industrial applications such as checking aircraft turbine blades for weaknesses).